Archaeozoology

Dr. Günther Karl Kunst

Archaeozoology (Zooarchaeology) is archaeology with animal remains. Animal remains, obviously, represent biological materials, and are also recognized as such by most archaeologists. Consequently, many archaeological expectations towards archaeozoology focus on issues related to this „biological“ content: reconstructing former environments and, e.g., historic breeds of domestic animals.

More generally put, archaeozoologists studie the roles of animals in past human societies. Among these, acquisition and production of meat and other animal products, and human consumption habits, range among the most obvious. Crafts activities, belief and semiotic systems and rituals may likewise become apparent from the analysis of animal bone assemblages.

To reduce archaeological animal remains to their „biological“ content would largely underscore their potential and analytic/heuristic value in categorizing and interpreting sites and contexts. Both, individual remains and whole samples, represent also artifacts, since past human societies have produced and/or dealt with them. This dealing may comprise the whole life cycle of an object, e.g., from production and use until discard and disposal. It is by the composition of samples that past human behaviour may become apparent: specific human acitivities are likely to generate specific animal bone assemblages.

Certainly, samples are not only shaped directly through intentional human behaviour, but also by „natural“ conditions, like weathering, soil condition and the mere physical characters of archaeological contexts (e. g. pits vs. living floors).

Taphonomy, a palaeontological (hence geo-scientific) discipline, explores the creation, build-up and subsequent fate of assemblages. Primarily designed for fossils, it can also be applied to most archaeological find categories, even artifacts proper. In archaeozoology, it may be justifiably regarded as the main source-criticism. Studies of skeletal part representation, fragmentation, butchery marks and spatial distribution belong to its methodological repertoire. In some ways, archaeozoology can be regarded as applied taphonomy of animal remains in the anthropogenic sphere.

Zooarchaeology is mainly about relative data

(Umberto Albarella, ZOOARCH e-mail list, february 2015)

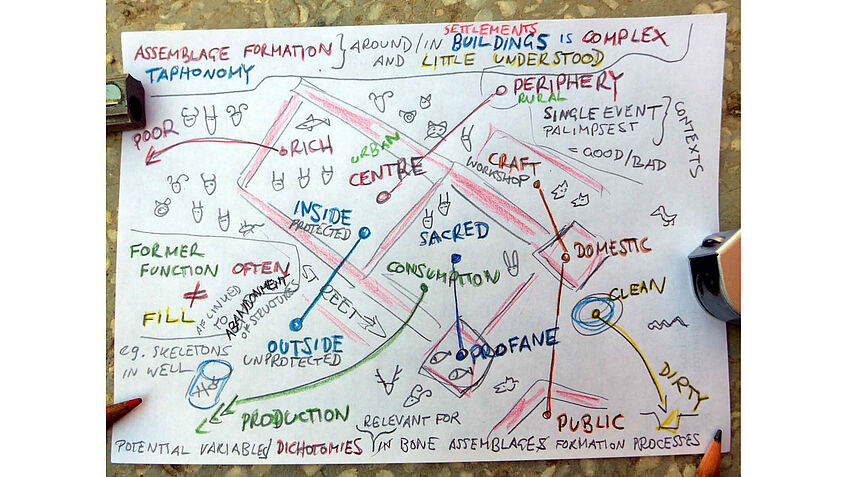

Archaeozoology probably unfoalds most of its explanatory potential in intra-site analysis. As soon as there is a decent amount of animal bone samples, it is possible to use them in deciphering site formation processes and in interpreting functions of archaeological structures. Human activities and other influences are always likely to create a certain patterning (a „bonescape“) across a site. (see picture for potential reasons for patterns and gradients). It is these bonescapes we are after, the ultimate signal for any further interpretation, not the individual bone. Principally, this approach (searching for patterns) is comparable to data collection in geophysical prospection and similar disciplines. The informative value of animal remains is often complementary to pottery, the other large category of archaeological finds in settlements. As Terry O’Connor has put it (personal comment, june 2017), pottery may be a bad predictor for animal remains. The mutual relationship of these two important groups of finds remains largely unexplored!

Real interdisciplinarity in archaeology is achieved when scholars of these different fields work together in the interpretation of archaeological structures.

It goes without saying that archaeozoological research does only make sense if excavations have been carried out properly, and contextual information is available and accessible.

In contrast to physical anthropology, archaeozoology has ist emphasis in settlement archaeology, although animal remains may also appear as grave goods, and even animal cemeteries are known, from battlefield sites and elsewhere.

A compilation of sensible introductory literature can be found here.