Research focus and ongoing projects

Subdivision - by periods

With the exception of the Paleolithic, animal remains from all prehistoric and protohistoric periods of Austria are studied by the VIAS archaeozoology research area. Due to the existing cooperation and the available material, however, certain regional and chronological priorities arise. The processing of animal remains from Austrian paleolithic excavations is currently coordinated by Florian Fladerer at the Institute of Paleontology at the University of Vienna.

Neolithic

In recent years, samples of various Neolithic cultures from Lower Austria (Stoitzendorf, Furth near Göttweig) have been processed. These are mostly from rescue excavations and were transmitted among others by the association ASINOE.

Bronze Age

Meat supplement (sheep culter) from a cemetery of the younger urnfield period - Franzhausen, Lower Austria)

Bronze Age

For some time now, there has been a cooperation with the Prehistoric Commission of the Austrian Academy of Science, focusing on the urnfield period: Oberleiserberg (settlement), Nussdorf / Traisen (burial ground).

Iron Age

Burial grounds: Führholz in Unterkärnten, Wöllersdorf, Lower Austria (in planning).

Settlements: Prellenkirchen (cooperation Bundesdenkmalamt).

Roman Empire and late antiquity

The provincial Roman period has long been a special focus of VIAS. Thanks to the high amount of findings, it is possible to examine not only chronological developments, but also different social milieus on the basis of bone waste. Three current or recently completed projects are therefore presented in more detail:

Eastern vicus of Mautern/Danube (Lower Austria)

Link, Roman Empire and late antiquity

Like the already published bone samples from the fort of Mautern - Favianis, the substantially more extensive material from the excavations of the ÖAI in the years 1997-99 gave the opportunity to study the connection between findings, meat consumption and animal species composition.

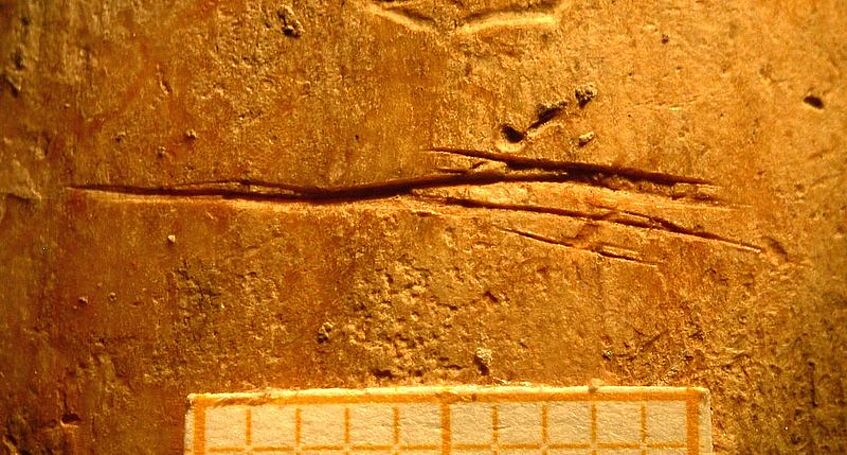

Although the latter is rather monotonous - there are almost only bones of domesticated animals available - the remains themselves testify to an intensive human use: the proportion of bones with cutting traces and other surface marks is very high.

Especially the bovine bones show numerous indications of the consumption of smoked or otherwise preserved meat.

Local pig production, on the other hand, is evidenced by concentrations of unprocessed skeletons of very young piglets.

The extremely extensive material required a rigorous selection of materials, giving preference to some closed, well-dated archaeological objects.

With the slaughtering of large quantities of cattle on a regular basis in the vicus, the re-use of certain waste products for tool production (such as bovine pebbles as sledges) could also opportunistically develop. From a socio-historical point of view, the inhabitants of the vicus can be addressed as a probably less privileged group, partly dependent on supply, partly self-producing.

Civil town Carnuntum, canal system and road substructure in the area of the western road (Lower Austria, archaeological park Carnuntum)

Link, Roman Empire.

A very different social milieu than in Mautern is tangible by the bone waste from a canal filling and other findings from the substructure of a street in the civilian city of Carnuntum.

The material was apparently embedded very quickly and therefore shows little traces of impoverishment or destruction processes - it should largely correspond to the waste association that had developed at that time.

The remains of farm animals show a high degree of selectivity as far as the selection of skeletal remains is concerned.

Thus, skull and claw elements, as well as pieces of ribs from the cattle are found.

In terms of distribution history, the occurrence of the house rat is remarkable.

The burial ground of Halbturn (Burgenland)

Link1, Link2, Roman Empire and late antiquity.

The animal bone material from burial ground of Halbturn (excavated since the late 80s), which belongs to a nearby villa rustica, provides a good example of how the zoological findings can extend the interpretation of a locality: the sometimes quite complicated structures (grave garden, small ditch, irrigation ditches) of the area primarily perceived as a necropolis were used to receive animal waste, which can be interpreted only in part as funerary objects and therefore can be associated with the funerary rituals.

Mostly skeletons, parts and their residues of apparently not consumed, but at best skinned species (horses, and dogs, but sometimes also cattle) can be found. By contrast, the proportion of bones that have undergone a consumption process and show corresponding surface markers is very low. Many bones show traces of fire. It is one of the unanswered questions arising in the treatment of this material, whether the bone accumulations can be related to the cult of the dead or to special sanitary measures in the context of "cleansing" of the terrain. The otherwise low degree of destruction, especially of the long bones, allows a good biometric detection of the Roman farm animals in the area. As an indicator of the presence of an enhanced or particularly "romanised" population group, the occurrence of toy dogs can be considered.

Middle Ages and modern times

Herbert Böhm is currently studying animal remains from the early medieval cemetery of Frohsdorf (Lower Austria, FWF project P16593) and an ancient and medieval mining settlement near Hüttenberg (Carinthia, FWF project P16069 "Ferrum Noricum Hüttenberg", head B.Cech).

Animal bone specimens from late medieval and early modern monasteries and town centers (Kartause Mauerbach, Dominican convent Tulln, Vienna - Alte Universität and Herrengasse) prove to be particularly rewarding, because they provide immediate insight into the methods of food preparation and the identity-forming significance of some animal species (fasting meals, including turtle).

Working traces - cutting process

Animal bones "draw" well, because they are

- hard enough or sufficiently mineralized to stand the test of time in the soil

- but on the other hand also sufficiently soft, so that they are damaged by harder substances and keep these traces in their fossil state.

For this reason, traces of work, which are left by stone or metal tools, show on bones in a characteristic way.

Human activities performed on the carcass are therefore comprehensible. In favorable cases, even entire courses of action ("chaîne opératoire") can be followed from skinning and cutting to food preparation and disposal. Which other archaeological find material can give so much information about processes?

Bone artifacts - a call!

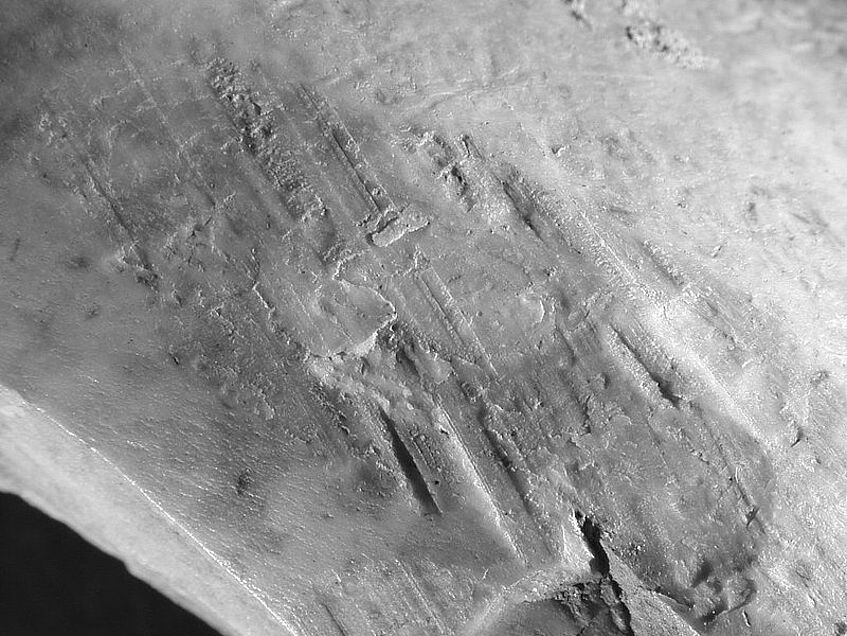

Until the Industrial Revolution, hard animal substances (bones and teeth) played an important role in the production of commodities, in many cases where plastics or light metals are used today. Hence the prejorative term "plastic of primeval times".Since these are often simple and unspectacular forms, it is often assumed that up to 30% or more of the bone tools of a find complex are first assigned to the zoological material and usually remain there because no side (zoology, small finds) really feels responsible. Conversely, in some collections, completely innocent animal bones are specified as artifacts, because their shape is reminiscent of certain devices. Here, interdisciplinary communication is a necessity, a whole group of finds is otherwise systematically undervalued!An impressive example would be skids, which were made of cattle pines (jaw skid, sledge runners made from the lower jaw pair of a domesticated cattle, Mautern / Favianis). This type of device appears to be widespread in some provincial-Roman and Iron Age situations, but has not usually been perceived as an artifact until now, because the changes in the bone itself are relatively small.Please also note the following articles

Download PDF - Sledge runners made of cattle mandibles? – Evidence for jawbone sledges from the Late Iron Age and the Roman Period in Switzerland and Austria

Download PDF - From Hooves to Horns, from Mollusc to Mammoth, Manufacture and Use of Bone Artefacts from Prehistoric Times to the Present